آب سالم تر سلامت بیشتر

Many African cities have had to take drastic measures in recent years to tackle water shortages. Cape Town’s historic shortage in 20 is fresh in our minds. South African authorities narrowly avoided disaster by rationing drinking water to 50 liters per inhabitant per day in a city that was used to consuming large volumes of water.

That same year, Bouaké in Côte d’Ivoire received emergency financing of $8.5 million from the World Bank to cope with a serious water shortage. The intervention solved the shortage by building two compact water treatment plants, boring and fitting 20 new wells, rehabilitating 82 hand pumps in the villages connected to the city’s water system, and distributing safe water by water tankers.

Water, sanitation and hygiene central to the COVID-19 crisis

The World Health Organization’s number one recommended protective measure against the coronavirus is to wash hands frequently with soap. Ensuring the availability of safe water for all is clearly vital to keep up the fight against the spread of COVID-19 and future pandemics.

Yet in Sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 63% of people in urban areas, representing the main clusters of the virus, find it hard to access basic water services and cannot wash their hands. An estimated 70% to 80% of the region’s diseases are attributable to poor water quality. Dysentery and cholera, for example, are among the leading causes of infant mortality.

African governments have now put in place rapid response plans to combat the COVID-19 emergency. Yet most of these plans concentrate on the immediate health care response and focus less on improving access to water and sanitation, other than outfitting health centers and other public places with handwashing facilities.

Rapid urbanization calls for sustainable solutions to improve access

The crucial issue of access to safe water is especially important in a region facing rapid urban growth. By 2050, over 1.6 billion Africans will be living in cities and urban slums. The coming years will see populations doubling in some 100 major cities. Some, such as Lagos in Nigeria, with its 23 million inhabitants today, and Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with 12 million, are megalopolises already. The world will also see other pandemics. And climate change will increase the episodes of drought.

Hence it is vital for African governments to put strategies in place, earmark part of their budget, and develop policies to supply water, sanitation, and hygiene services for all their people. A number of solutions are available to them:

Increase investments in water and sanitation: To meet Sustainable Development Goal 6, Africa will need to invest massively in the water and sanitation sectors over the next 10 years. Some $10-15 billion a year will be needed to supply the entire population with safe drinking water and provide basic sanitation service. Currently, African countries allocate no more than 0.5% of their GDP to the sector and invest only a very small proportion of international assistance in this area.Guarantee the financial viability of water utilities: A recent World Bank study on the performance of water supply services in Africa finds that half of the region’s utilities do not have the revenues to cover their operation and maintenance costs. Countries urgently need to build up the operational capacities and resilience of both public and private utilities to be able to supply sufficient volumes of high-quality water. And they need to do this at a politically and socially acceptable tariff while remaining financially viable.Re-use wastewater: For many countries, wastewater management has become an important way to meet the demand for water, especially around urban areas where market gardens are being developed and providing vital food supplies to city residents. In Israel for example, 91% of wastewater is treated, and 71% of it is then used to irrigate crops. In African countries, however, just 10% of wastewater is treated. An increase in the reuse of it to irrigate cropland could secure the region's food security

as countries apply circular economy approaches to water security

Today’s historic health crisis will deal a long-term blow to the global economy, but it will hit the fragile African economies even harder. The faster these economies respond, the more resilient they will become. A sustainable response to COVID-19 and the pandemics that will follow must include a focus on water and sanitation.

.

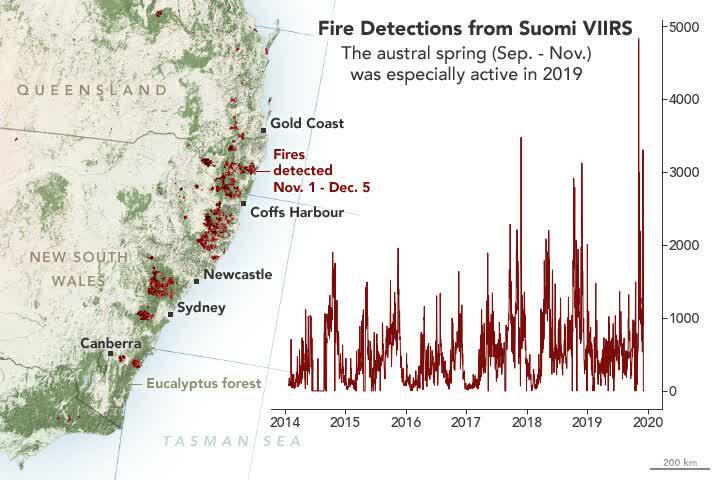

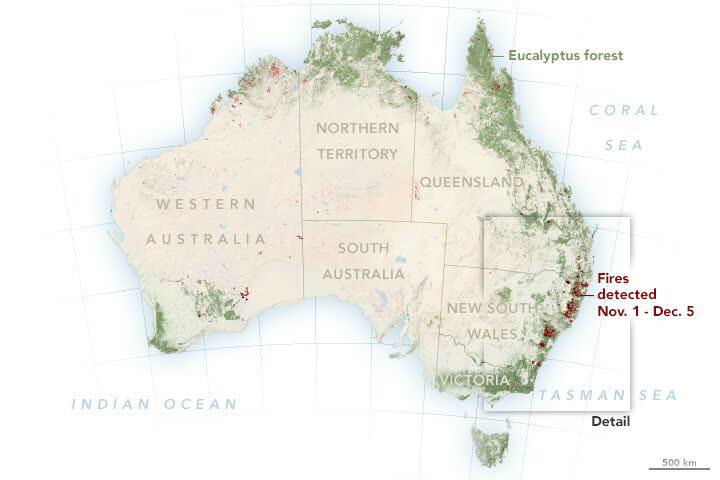

The fire season in New South Wales normally ramps up in December. In 2019, unusually hot weather and a potent drought primed the region for a roaring start in October. Two months later, more than 100 fires are still raging in forests and bush areas near the southeast coast, including some subtropical rainforests and eucalyptus forests that do not often see fire.

By December 12, 2019, fires in New South Wales had charred 27,000 square kilometers (10,000 square miles), an area about the size of Maryland. Vast plumes of smoke and pollution have streamed from fires for weeks, enveloping coastal towns and cities with toxic haze and smoke. Parts of Sydney, a city of 5 million people, recently endured pollution levels several times above what is considered hazardous, according to news reports.

The fires have been particularly damaging to eucalypt forests and woodlands, which thrive in areas of relatively dry and nutrient-poor soil. These forests are prone to big outbreaks of fire because many of the trees species have oil-rich foliage that is extremely flammable. The map above, based on data from Australia’s Department of Agriculture, shows the range of eucalypt forests. Red dots show the locations of fires as detected by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite between November 1 and December 5, 2019. The natural-color image was acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite on December 9, 2019

Fires actually help many eucalyptus species release their seeds and germinate. During a fire, their woody capsules empty their contents onto a nutrient-rich ash seedbed from which all the understory competition for light, water, and nutrients has been removed,” explained Ayesha Tulloch, a University of Sydney conservation biologist. At the wrong time — such as in this case — fires can be devastating for eucalypt forests.” A lack of rain before or after a blaze can sharply limit seed germination.

The effects of fires in eucalyptus forests ripple through the animal kingdom. Browsing animals like kangaroos are driven out by fire for a short time, and the heat-treatment of soil reduces the number of plant-eating insects and soil organisms during the early growth period,” said Tulloch. Many koalas, which are slow moving, have been affected or even killed by fires in 2019. But the range of the koala covers most the east coast of Australia,” she said. Relative to its range, the fires are relevant to only a very small proportion of the existing koala population in Australia.”

Though normally immune to fire because of moist conditions, the drought and hot temperatures of recent years have made rainforests and wet eucalyptus forests vulnerable. Rainforest systems from Australia’s northern wet tropics, to Lamington National Park, to alpine montane ecosystems have experienced massive fires,” said Tulloch. These systems cannot tolerate fire, and most plants are killed by it,” adding that they will not recover nearly as quickly as dry eucalyptus forests can.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens and Lauren Dauphin, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Eucalyptus forestry data is from Australia's State of the Forests Report 20. VIIRS fire location data from the Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS). VIIRS trend data from the University of Maryland. Story by Adam Voiland.

.

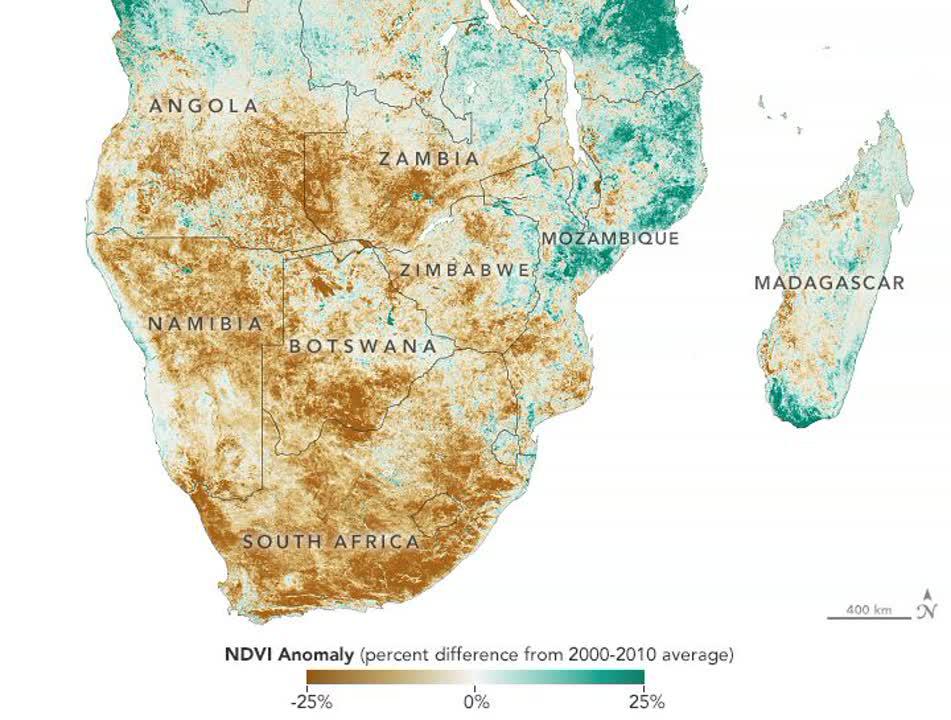

Southern Africa is suffering through its worst drought in several decades and perhaps a century. Diminished and late rainfall, combined with long-term increases in temperatures, have jeopardized the food security and energy supplies of millions of people in the region, most acutely in Zambia and Zimbabwe.

According to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC), at least 11 million people are facing food shortages due to drought. Grain production is down 30 percent across the region; in Zimbabwe, where they are close to running out of their staple crop of maize, it is down 53 percent. Livestock farmers in southern Africa have suffered losses due to starvation and to early culling of herds forced by shortages of water and feed.

This year’s drought is unprecedented, causing food shortages on a scale we have never seen here before,” said Michael Charles, head of IFRC’s Southern Africa group. We are seeing people going two to three days without food, entire herds of livestock wiped out by drought, and small-scale farmers with no means to earn money to tide them over a lean season.”

The natural-color images above were acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites. The first/left image shows Lake Kariba, one of the world’s largest reservoirs, on December 2, 20; the second image is from December 1, 2019. While the landscape is browner in 20 (a hint at the long-term drought), the extent of the lake is greater than in 2019. Use the image-comparison slider to see the differences in the shorelines.

The map above depicts anomalies in the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a measure of how plants absorb visible light and reflect infrared light. Drought-stressed vegetation reflects more visible light and less infrared than healthy green vegetation, and this can be detected by satellites. This NDVI anomaly map, based on data from Terra MODIS, compares the health of vegetation in southern Africa from the dry season in 2019 versus the same period from 2000-2010. Brown areas show where plant health or greenness” was below normal. Greens indicate vegetation that is more widespread and abundant than normal.

According to meteorologists, October rains were late in 2019 and precipitation has been below normal this year. In fact, decreased rainfall and drought has been a persistent problem for several years, as the dry season has been growing longer and hotter. According to the World Food Program, southern Africa has received normal rainfall in just one of the past five growing seasons.

Water levels on the Zambezi River are lower than they have been for decades, fish stocks are in danger of collapsing, and the usually thundering Victoria Falls has slowed to a trickle. The depletion of the river has endangered hydroelectric Kariba Dam, which usually supplies about half of Zambia and Zimbabwe’ electricity. Lake Kariba stands somewhere between 10 and 20 percent of capacity and at its lowest point in more than two decades. Water levels are just barely above the amount needed to keep the hydroelectric plants running. Water levels typically begin to rise in January and February when wet season rains start to accumulate across the watershed.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS/LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Michael Carlowicz

عبدالله فاضلی» روز شنبه در گفت و گو با خبرنگار اقتصادی ایرنا افزود: تاثیر نفوذ بارش های سال آبی سال گذشته (مهرماه۹۷ تا آخر شهریور ۹۸) دربسیاری از دشتهای کشور ( جزو دشتهای ممنوعه و عمده در فلات مرکزی، شرق و شمال شرق) با تاخیر بیش از پنج ماه همراه بوده و به دلیل ضخامت، قسمت خشک آنها همچنان زیاد است.

وی ادامه داد: بر این اساس بارش های پارسال در این دشت ها موثر نبوده و همچنان روند خشک در آنها ادامه دارد و یا نهایت اندکی بهبود داشته است.

فاضلی خاطرنشان ساخت: اگرچه بارش های سال آبی سال گذشته خوب بود اما بخش کمی از آبخوانهای کشور را تحت تاثیر قرار داد.

مدیر کل دفتر حفاظت و بهرهبرداری منابع آب و امورمشترکان شرکت مدیریت منابع آب ایران گفت: بارش های پارسال هم از نظر زمانی و هم از لحاظ مکانی بسیار متفاوت بود و برای ارزیابی تاثیر آنها در سفرههای زیر زمینی هرساله و در پایان مهر ماه اقدام میشود.

وی ادامه داد: بنابراین نتایج بارش های سال آبی مهرماه ۹۷ تا آخر شهریور ۹۸ نشان میدهد که متوسط ارتفاع بارشهای این سال نسبت به سال ماقبل آن(مهرماه ۹۶ تا آخر شهریور ۹۷) که سال کامل خشکی بود ۱۰۰درصد افزایش داشت.

فاضلی افزود: بارندگیهای این سال نسبت به دوره دازمدت ۵۰ ساله نیز هشت درصد رشد داشت که نشان دهنده سال پربارش بود.

مجری طرح احیاء و تعادل بخشی منابع آب شرکت مدیریت منابع آب ایران ادامه داد: اما وضعیت بارش های این سال به لحاظ مکانی بسیار متفاوت بود . بیشترین سهم بارش در ۶ حوضه آبریز درجه دو کشور شامل تالش، سفیدرود، کارون بزرگ، هراز و قره سو، مرزی غرب و کرخه رخ داد.

فاضلی افزود: حدود هشت درصد مساحت کل دشت های کشور در این حوضه های آبریز قرار دارد.

به گفته وی، مجموع حجم تغذیه ای که ناشی از بارش های سال قبل بر آب خوان های کشور صورت گرفت حدود دو میلیارد متر مکعب است.

مدیر کل دفتر حفاظت و بهره برداری منابع آب و امورمشترکان شرکت مدیریت منابع آب ایران ادامه داد: برآیند مثبت بارش های پارسال در کل کشور سبب شد که سهم کسری سالانه مخازن سفره های زیر زمینی که پنج و نیم میلیارد متر مکعب است حدود نیم میلیارد بهبود یابد.

فاضلی افزود: بنابراین بارش های پارسال کسری سالانه مخازن سفره های زیر زمینی را نیم میلیارد متر مکعب کاهش داد.

وی آبخوان های تحت تاثیر را آبخوان های واقع در نواحی غرب، شمال غرب و نواحی شمالی دانست که وسعت کمی هم به خود اختصاص داده اند.

- رویای بیت کوین Bitcoin Dream

- پرسش و پاسخ وردپرس

- سایت کیم کالا فروشگاه اینترنتی

- Lotus Water

- Psychology

- سایه وارونه

- داده پردازی نرم افکار

- اپیکیشن نت مانی net money

- مرکز تخصصی گچبری و قالبسازی آذین

- بیوگرافی

- ابوالفضل بابادی شوراب

- گروه هنری اولین اکشن سازان جوان

- اقیانوس طلایی

- .:: تنفّس صــــبح ::.

- شین نویسه

- خبر

- شهدای مدافع حرم

- پایکد

- نقاشی کشیدن

- درمان مو

- کبدچرب

- Sh.S

- نمونه سوالات استخدامی بانک تجارت (فروردین 1400)

- رسانه ارزهای دیجیتال و صرافی Coinex

- مرکز ماساژ در تهران

درباره این سایت